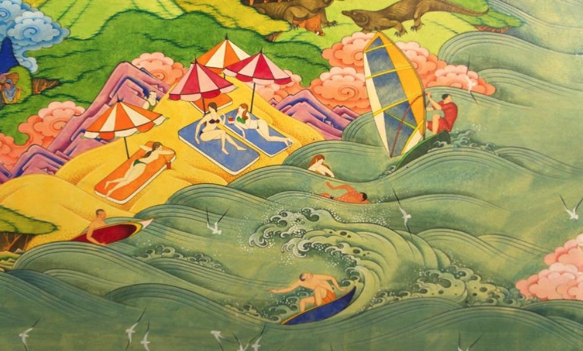

Mongol (uran) zurag (US: /ˈmɒngɒl ˈdˈzuːrɑg/ lit., “Mongol painting”) is one of the most eminent, long-living art movements in Mongolian visual art history. Countless gifted artists continue to create in this genre that uniquely expresses the Mongolian nomadic philosophy through thin fluid colors, fine contours and delicate motifs applied on a cloth canvas to present a flattened and thorough composition. Whether it is the landscape of a countryside with a bird’s-eye perspective or the portrait of a figure in his or her milieu, Mongol zurag artworks tell a story through actions that seem to be taking place simultaneously in the past, present and future.

The archetypal masterpiece of Mongol zurag is “One Day in Mongolia” (176x136cm, 1911-1912) by B.Sharav (1869-1939). It is with this painting that Sharav, who was trained as a Buddhist monk and working as a court painter for Bogd Khaan, perhaps having sensed the imminent political changes, breaks away from the traditional religious genre and portrait paintings of aristocrats to depict the ordinary life of his people in the diverse strata of his society. “One Day in Mongolia” is like a naturalistic snapshot of more than three hundred characters engaged in common activities that an average person living in any given region of Mongolia would have experienced from birth to death at the beginning of the 20th century. The subject matter was unremarkably quotidian, even boorish at places; and the disproportionately large size of the people and animals against the background of nature added a comical tone to the radically undistinguished theme. Yet Sharav’s impeccable fluency in the technique of Mongol zurag, and the wide scope of his composition covering the entire geographic territory of Mongolia revealed the painting to be as stately as any image of a deity, a work of a true master. Art historian B.Bayartur wrote that the bemused Bogd Khaan upon getting a hearty laugh out of his newly commissioned painting gave Sharav the nickname Marzan (lit., “funny”).

One cannot help but wonder how Bogd Khaan and Marzan Sharav might have reacted to the recently unveiled marvel of Mongol zurag, an astonishing 21×2.5m large cloth canvas showcasing the whole world through the reverent eyes of artist N.Sergelen and his three devoted students S.Ganzam, Sh.Sainzul and N.Khosbayar. Over a century after the creation of Sharav’s original masterpiece that changed the course of Mongolian art history “One Day of the World” (1998-2019) was created in homage to the chef-d’oeuvre and is an important milestone in the history of Mongolian fine art. First, the sheer size of the composition makes it the largest Mongol zurag painting produced in this genre for all the past time until today. Second, it is the artistic detail, rendered true to the genre’s custom on every square inch of the canvas, not to mention the unique approach to the coordination of the individual subjects with the traditional color scheme that conveys the harmony of the work as a whole. Third, it is the astounding volume of collective knowledge, the overwhelming amount of information available all at once. The combination of these elements presented in the painting impresses the viewer who might simultaneously feel intellectual overload, a flood of memories and a tug of wishful aspiration.

“One Day of the World” could be visually divided into eleven sections, taking the viewer on a fascinating journey through symbolic representations of the flora and fauna in various regions of the world, as well as the landmarks and traditional activities of the people of over 190 countries in North America, Europe, Middle East, Central Asia, East Asia, Australia, South America and Africa (from left to right). I asked professor Sergelen how he chose the placement of the countries and their icons on the composition, wondering if perhaps there is a hint of visual commentary on the geopolitical state of the world. After all, Ulaanbaatar’s landmarks and Mongolian traditional activities are placed on a significant area in the upper center of the composition. With an understanding gaze that a wise teacher makes, the professor kindly explained that his placement of Mongolia in the composition’s center was a lucky coincidence because first he laid out the countries located north of the equator beginning as far west as possible. Then, after reaching the far South East, Australia naturally filled the remaining space on the bottom of the canvas. So, he continued drawing further and further east, visually circling the world for the second time until the countries located south of the equator were laid out.

Professor Sergelen chuckled as he remembered his eight-year-old daughter Sarnai’s remark: Disneyland is missing! He wanted to paint more images but ran out of space, so he first selected the representative symbols that could not be overlooked. Then, he decided on the layout according to Mongol zurag tradition, which moves away from hierarchy and emphasizes the harmony between nature and people through the accordance of color. As he gathered information from books, encyclopedias, National Geographic magazines and the internet during the nine years of research and twelve years of painting while also working at the University of Culture and Arts and creating other works to sustain his family, he learned that every place and cultural heritage in the world is unique and awe-inspiringly beautiful, and that in the end, we are all the same even if we live in different corners of the world.

When asked if there were times when he wanted to quit, Professor Sergelen replied that the thought of quitting never crossed his mind, although he felt intellectually exhausted towards the end. He said that creating a picture of the world on one plane felt as if he were caring for a newborn for over twenty years; that it was his duty as an artist to make something useful for people, to share the heritage of Mongol zurag with the world, to bring aesthetic joy to the viewers but also to intellectually enrich them, and to spread the love for Mother Earth. With the generous support of his friends S.Erkhembayar and N.Ganbaatar, his three talented students and the seamstresses who created the dark blue silk frame for the painting, artist N.Sergelen’s friendships, hard work and dedication were the fuel to his resolve to deliver a new landmark in Mongolian fine art. His painting and the process of its creation is an inspiring success story for future generations of Mongol Zurag artists to come. In conclusion, one is tempted to believe that Marzan Sharav and Bogd Khaan would have chuckled with awed approval of his achievement.

“One Day of the World” was on display at the Union of Mongolian Artists until January 4th 2020. Thereafter, it will be shown in its permanent home in Chinggis Khaan Art gallery.

By Ariunaa Jargalsaikhan

Published in UB Post on December 30, 2019

Ulaanbaatar