Paper is one of the simplest, most accessible yet most capricious of media. Perhaps it is this property that enables papercut art to attract a broad range of viewers: women and men, children and the elderly. It cannot leave one indifferent, because the effect of lightness and delicacy requires the artist to dedicate so much time and painstaking concentration that the viewer is mystified by the incredible patience and talent that it takes to carve out such a graceful work of art.

Since the invention of paper around 100 BC in Ancient China, where the art of papercutting first originated, craftswomen and men around the world have been using paper as a medium for creating beautiful works of art. Today, the wealth of world traditions, symbols, ornaments and tales seeps through the timeless medium as almost every culture hails its unique tradition in the art of paper cutting.

And even though papercut art has predominantly been relegated to the realm of applied and decorative arts, great artists such as Joanna Koerten, Henri Matisse, Kara Walker and many others have memorialized the subtle power of papercut art in their oeuvre. Presently, notable artists such as Vanshika Agarwala, Tahiti Pehrson, Parth Kothekar, Rogan Brown, Riu, Elsa Mora, Yuko Yamomoto, Suzy Taylor, just to name a few, have been continuing to establish the important place that papercut art is holding in the canon formation of art history. As more and more artists around the world create and share their fascination with the complexity of the seemingly simple art of papercutting, so too in Mongolia, artists could perhaps cultivate this intricate form of art.

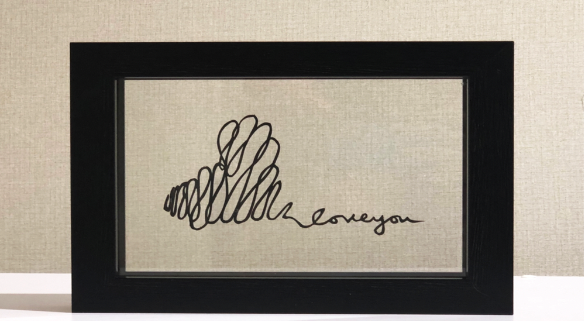

Graphic designer and papercut artist, E. Indra’s art is like an intricate tapestry of meticulously crafted designs. Using a precision knife, she cuts out texts and drawings from a single sheet of paper and places them in between glass panels. The space between the back of the frame and the outline of the piece suspended inside the glass allows for her elegant papercuts to cast distinct shadows onto the background. In this way, the light echoes her creation on another surface. The result has a striking effect: a contrast between a delicate pattern and its sharp impression, a seemingly fragile piece that emanates boldness and strength.

Indra first began to create paper art in 2014. She applies different techniques to develop her own style. Sometimes she bends her papercuts (Connection 80×62; River Stones 68×83; Current 68×83) presenting the sculpture-like fluid quality of the medium. She also applies line drawing (Wind), fluid painting (Sunflower; Leaf; Lilies; Hibiscus), splatter painting (Thought; Eagle; Message; Girl with Roses), spray painting (Hummingbird) that are usually completed with vivid colors. These techniques often serve to highlight the backgrounds and/or her main subjects in order to achieve the contrast that could characterize her style.

Besides the aesthetic qualities that Indra’s art undoubtedly communicates, it also raises important questions regarding issues on mental health and intimate partner abuse, which have long been considered taboo to discuss in Mongolian society. As she witnessed several visitors tearfully gaze at the Butterfly caught in a spider’s web, she expressed that unfortunately our society conditions many men to believe that if they have the financial power, they are entitled to mistreat their partners, which becomes a source of much suffering for the women and children in our society.

In the sacred space of the Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts, from 11th-17th November 2019, sojourned Indra’s debut solo exhibition titled, Connection. People are all connected, she told me, if our history preserved by this museum and the visitors to its exhibitions can relate to a single piece of my art, then they have connected with me. As to the beautiful soul that’s entangled in the web of nightmarish realities, Indra’s art seems to gently whisper, “I see you. I am with you. We are valuable.”

By Ariunaa Jargalsaikhan

November 20, 2019

Ulaanbaatar