Part 2 of 3

Undur Gegeen Zanabazar is one of the most influential figures in Mongolia’s Buddhist history. He was the first Bogd Gegeen, a 17th-century Head of State and Faith. For a long time, Zanabazar was blamed for Mongolia’s submission to the Manchurian Empire. However, as an intellectual leader, he is renowned for having ushered the nation into a cultural renaissance. A closer look at the historical background of Buddhism in Mongolia and Undur Gegeen’s life could provide a deeper understanding of why Zanabazar’s work is an integral part of Mongolian art history.

During the Yuan period (1271–1368), free trade and extensive cultural exchange influenced the fusion of artistic styles throughout Asia, and the undercurrent of Central Asian nomadic aesthetics could be felt in Asian sacred art.1 By the 1260s, Khubilai Khaan had chosen to consolidate power over the vast Mongol state through the acceptance of an organized and sophisticated religion.2Tibetan Buddhism had been acclimatized to its shamanic roots since the 8th century. It had a powerful intellectual and cultural appeal to the Mongol emperor, who became a Tibetan Buddhist himself. Abundant cultural exchange enabled the talent and mastery of Nepalese and Pali artists to become influential to the practice of Buddhist art in this period.3

After the fall of the Yuan dynasty, Mongol princes of various khanates continued to uphold their spiritual alliance with Tibet.4 In 1578, Altan Khan of the Tumed Mongol nation, a 17th-generation descendant of Chinggis Khaan, bestowed a reverent title on the third leader of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism.5 The leader’s name was Sodnomjamts, or Sonam Gyatso in Tibetan – Gyatso meaning “ocean.” He was thus named “Dalai Lama,” by which the lineage later became known throughout the world, and the title was applied to the first two incarnations retrospectively.6 Such bestowing of reverent titles upon important figures was one of the mutually friendly gestures that have been, for a long time, a traditional strategy of upholding a cultural and political alliance between Tibet and Mongolia.

Seeing the formidable effects that Buddhism had on the intellectual and spiritual development of Altan Khan’s people, his distant relative, Abtai Sain Khaan of the Khalkha Mongols, visited in 1585 to meet the third Dalai Lama.7 A year later, on the foundations of the first capital of the Mongol Empire, Abtai Sain Khaan inaugurated Erdene Zuu, a Buddhist monastery with 62 temples and about 500 buildings for approximately 300 monks.8 It became the center of Buddhist religion for the Khalkha Mongol nation.

The Mongols’ conversion to Tibetan Buddhism brought immense benefits for the ruling classes, helping them to maintain social order and hierarchy through moral guidance, medicine, and education. However, the mass formation of a new stratum of Mongol monks was too drastic a change for the warrior spirit of the descendants of Chinggis Khaan. In the wake of the Manchurian Empire (1644–1912), this lingering cultural identity crisis would become one of the root causes of Mongolia’s subjugation to the Qing dynasty.

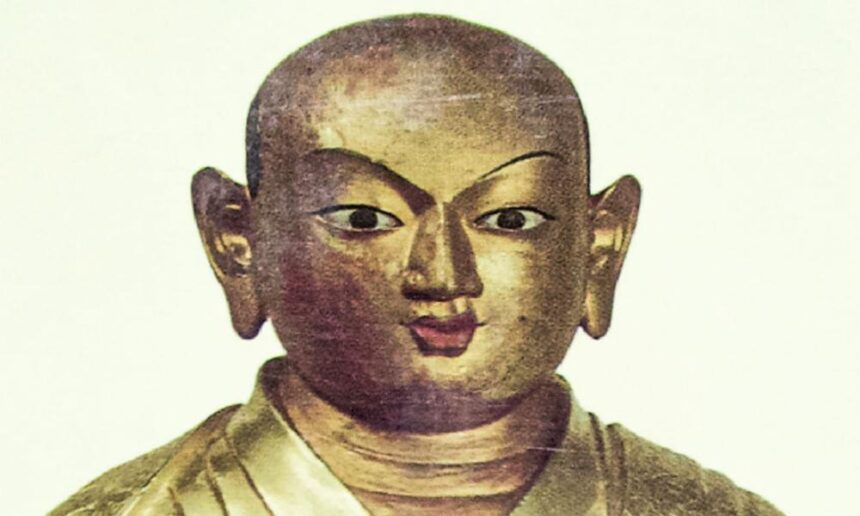

In 1635, Abtai Sain Khaan’s great grandson Ishdorj was born about 80 kilometers southeast of Erdene Zuu.9 He was a gifted boy who liked to read and recite Tibetan prayers from memory. He also liked to play by building temples with stones and pretending to conduct religious teachings. In 1639, at a convocation of Khalkha nobles, this four-year-old boy was proclaimed Undur Gegeen (High Saint) and initiated into the first order of monkhood by the Lama Jambal Bilig Nomun-khan. From that day, he was named Zanabazar, or Jnanavajra in Sanskrit, meaning “he who holds the thunderbolt scepter of wisdom.”10

When Zanabazar was fifteen years old, he journeyed to Lhasa to pursue his studies in Buddhism. In Lhasa, the fifth Dalai Lama recognized him as the reincarnation of Taranatha Gunga Ningbo (1575–1634), a famous Tibetan scholar and writer.11 Zanabazar thus became the first Mongolian, and the 16th in lineage, of Venerable and Excellent incarnate lamas, titled Javzan Damba Khutagt. This was a major historical event for the seven Khalkha nations. Consequently, Mongols celebrated the inauguration of their first Head of State and Faith, Bogd Gegeen, at a glorious Danshig Naadam festival.

When Zanabazar completed his studies at the age of 19, he returned home with a handsome suite of 40 skilled artists and learned lamas from Tibet. With the power of religion and state vested in him, the first Bogd Gegeen devoted his life to the peace and enlightenment of his nation. With his followers, he worked tirelessly to establish monasteries, build temples, create sacred art and a new alphabet – Soyombo Useg – and translate and write scriptures.12 Amidst tension and rivalry with neighboring khanates, Zanabazar sought to strengthen diplomatic relations with Tibet, Manchuria, and Russia.

The Undur Gegeen’s investment in soft power made him a much-loved leader among people who had been weary of repeated sudden attacks by warring princes over the years. Although Zanabazar’s vision of enlightenment and peace brought intangible value to Mongols, this seeming passivity did not sit well with warrior-rulers who aimed to restore the Mongol supremacy of the past.

One of them was Zanabazar’s older brother, Chakhundorj. He wanted to fulfill Abtai Sain Khaan’s mission of assimilating the Mongol Oirad nation into his own. In 1688, Chakhundorj and his only son died in a battle against the army of the Oirads.13 The Oirad Mongols had a fiercely resolute commander named Galdan Boshgot who had also studied Buddhism when he was young, under the tutelage of the fifth Dalai Lama, alongside Zanabazar. However, Galdan Boshgot had legitimate reasons14 to regard the Khalkhas’ alliance with the Manchus as an unforgivable betrayal of the Mongol moral code of autonomy.

As Galdan Boshgot’s army advanced eastward, it destroyed Erdene Zuu and many more monasteries along the way. Zanabazar and his people were forced to flee from their homeland and seek protection from the Manchurian emperor, Enkh-Amgalan. After 35 years in exile, Undur Gegeen Zanabazar passed away in Beijing in 1723, at the age of 88. As for Galdan Boshgot, during his third round of warfare in 1696, the Manchus sent an army of 200,000 men against Galdan Boshgot’s 30,000 brave fighters and his beloved warrior-queen.15 After Galdan Boshgot’s death, the Oirad Mongols heroically held out for over 60 years until the Manchurian Empire finally engulfed the whole of Mongolia under its hegemony in 1759.

Zanabazar was a talented scholar and an influential leader. Envisioning Mongolia as the northern center of Buddhist culture, he promoted peace and enlightenment in an era of extreme political instability in Central Asia. Today, Zanabazar’s masterpieces are a valuable demonstration of his efforts. A vital part of Buddhist art and history, they represent the culmination of diverse artistic traditions, styles, and techniques that were refined since the Yuan dynasty and concentrated in an extraordinary union of talent and craftsmanship. By expressing the human and divine qualities of the Buddha in exquisite harmony through his sculptures, Zanabazar revolutionized the outdated beliefs and ideologies of 17th-century Mongolian nomadic culture. For over two centuries after his death, Zanabazar’s work continued to inspire artists to create in the likeness of his masterpieces. His legacy lives on through the artists of the School of Zanabazar to this day.

References

- Syrtypova, S.-K. D. Zanabazar’s Style of Buddhist Art (Using Examples from the Collection of A. Altangerel). Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print, 2019. Pg. 13.

- Baabar, B. Монголчууд: Нүүдэл Суудал. Vol. 1. Ulaanbaatar: Admon, 2006. Pg. 123.

- Syrtypova, S.-K. D. Zanabazar’s Style of Buddhist Art (Using Examples from the Collection of A. Altangerel). Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print, 2019. Pg. 13.

- Kuzmin, S. L. “The Tibeto-Mongolian Civilization.” The Tibet Journal, vol. 37, no. 3, 2012, pp. 35–46. www.jstor.org/stable/tibetjournal.37.3.35. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Pg. 37.

- Tserendorj, Ts. “Алтан Хаан.” Монголын түүхийн тайлбар толь. https://mongoltoli.mn/history/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

- Richardson, H. E. Tibet and Its History (2nd ed., rev. and updated. ed.). Boston: Shambhala, 1984. Pg. 40., as referenced in wikipedia.org/Dalai_Lama.

- Tsolmon, S. “Абтай Сайн Хаан.” Монголын түүхийн тайлбар толь. https://mongoltoli.mn/history/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

- Chuluun, S. and Maralmaa, N. “Эрдэнэ Зуу.” Монголын түүхийн тайлбар толь. https://mongoltoli.mn/history/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

- Chuluun, S. “Занабазар.” Монголын түүхийн тайлбар толь. https://mongoltoli.mn/history/. Accessed 11 Apr. 2021.

- Syrtypova, S.-K. D. Zanabazar’s Style of Buddhist Art (Using Examples from the Collection of A. Altangerel). Ulaanbaatar: Admon Print, 2019. Pg. 325.

- Kuzmin, S. L. “The Tibeto-Mongolian Civilization.” The Tibet Journal, vol. 37, no. 3, 2012, pp. 35–46. www.jstor.org/stable/tibetjournal.37.3.35. Accessed 9 Apr. 2021. Pg. 37.

- Ibid.

- The character and quality of the relations between Zanabazar, his family, and his people are effectively conveyed with nuance in the biographical novel by Erdene, S. Занабазар (3rd ed.). Ulaanbaatar: Admon, 2012.

- In August of 1640, the Heads of Khalkha and Oirad States signed “The Forty and Four Code of Law.” The parties, in essence, agreed to support each other in standing firm against any foreign assault on the autonomy of Mongol states. However, neither the Khalkhas nor the Oirads fully trusted each other to honor this Code. The unresolved contention between Mongol khanates was a convenient shortcoming for neighboring states to exploit. The history of Oirad and Khalkha relations remains a subject of debate among historians to this day. The Oirad nation’s history is analyzed in depth by Dalai Ch. in Ойрад Монголын Түүх. Ulaanbaatar: 2002. As referenced by Tsogt, N. Personal interview. 04 April 2021.

- Dalai Ch. Ойрад Монголын Түүх. Ulaanbaatar: 2002. As referenced by Tsogt, N. Personal interview. 04 April 2021.

- Yelikhina, Yu. I. Сокровища Монгольской Буддийской Религии в Эрмитаже. Ulaanbaatar–St. Petersburg: Международная ассоциация монголоведения, 2020.

- Mongolian National Commission for UNESCO. In Commemoration of the 360th Anniversary of Undur Geghen Zanabazar, the First Bogdo Zhivzundamba Hutugtu, the Mongolian Great Enlightener, Outstanding Spiritual Leader and Statesman. Ulaanbaatar, 1995.

- Baasanjav, Z., Batbayar D., and Boldbaatar, Z. Монгол Улсын Түүх. Ulaanbaatar: МУИС, 1999.

By Ariunaa Jargalsaikhan

Published in UB Post on May 10, 2021

Ulaanbaatar