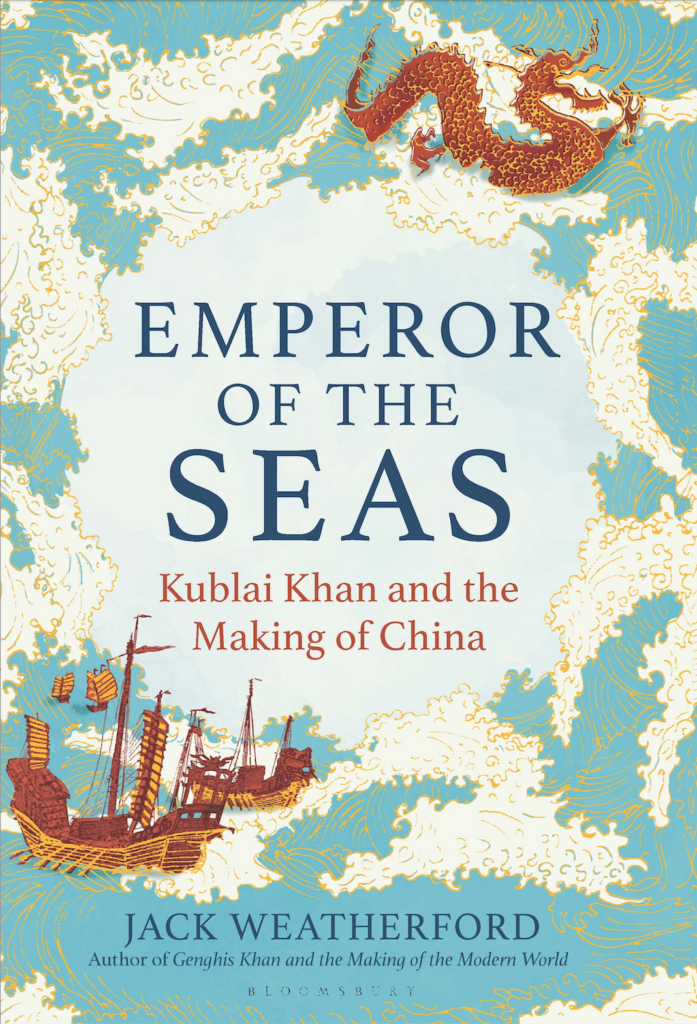

Jack Weatherford is a renowned cultural anthropologist, bestselling author and scholar on Chinggis Khaan. His books, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, The Secret History of the Mongol Queens and Genghis Khan and the Quest for God, have broken new ground in the global understanding of the impact of the Mongols on medieval history and the modern world. Mr. Weatherford’s writing, informed by his fieldwork expertise, enriches the historical non-fiction genre with a captivating style that takes readers on a journey to explore the lives of people whose histories were previously concealed in long-forgotten, cryptic sources. In 2022 he received the Order of Chinggis Khaan, the supreme decoration of the Mongolian State. His latest book, The Emperor of the Seas – Kublai Khan and the Making of China will be released on October 29, 2024.

AJ. Khubilai Khaan appears to be an even more enigmatic historical figure than his grandfather, Chinggis Khaan. In your book, you take readers on a historical journey that explores how Khubilai’s familial and environmental circumstances shaped his destiny as the founder of the Yuan dynasty and an extraordinary statesman of Asia. Could you provide us with a brief overview of how and why a Mongolian man from the landlocked steppes became the Emperor of the Seas?

JW. The success of Chinggis Khaan’s military tactics was perfectly suited for cavalry operations on land or in regions where rivers froze in winter, allowing skilled Mongol warriors to cross the ice. However, when they encountered vast bodies of water such as the Indus River or the Yangtze, new methods became necessary. Khubilai Khaan recognized that the South Song Dynasty could not be conquered without developing a navy. His innovative thinking allowed him to apply traditional steppe strategies to naval warfare, ultimately enabling him to conquer all of China.

AJ. What skills and ways of thinking from Khubilai Khaan can we embrace and apply in the modern world to honor the legacy of our ancestors?

JW. As demonstrated by both Chinggis Khaan and Khubilai Khaan, Mongolians have the ability to think in new ways. Unlike farmers, who are tied to the earth and face a limited set of challenges each year, nomads encounter a constantly changing array of conditions daily. They must navigate new terrain, deal with extreme weather, protect against predators, and live in small communities on the steppe, which requires them to think independently. While out with their herds, nomads often act alone or with just a few family members, solving problems as they arise.

These same innovative skills are crucial in today’s rapidly changing cyber world. Mongolians are well-suited for the modern technological age; they know how to think critically and adaptively.

AJ. Elon Musk recently shared a list of top ten books for “people who think about the Roman Empire every day.” Your book, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, was included alongside Hayek’s Road to Serfdom and other remarkable works. What do you think modern business leaders like Elon Musk gain from historical books like The Emperor of the Seas that may not be as apparent to the rest of us?

JW. I believe that innovative entrepreneurs see the Mongolian spirit embodied in both Chinggis Khaan and Khubilai Khaan. They recognize these great leaders’ ability to think with a global perspective, which parallels the traits exhibited by today’s most successful individuals.

AJ. Given that mining is currently our largest source of revenue, how can we preserve our nomadic heritage while showing reverence to Mother Nature? Could you share your thoughts on how to approach the challenges of urbanization alongside the preservation of nomadic traditions?

JW. This is a challenging question for me, as I lack the specific knowledge to provide a detailed answer. Throughout history, Mongolians have been very protective of their land and waters. Because of this, I believe that Mongolians can find the right balance on their own, without needing much outside advice. Only the Mongolians truly understand their country and environment.

AJ. Mongolian names and terms, such as the Hunnu Empire, Chinggis Khaan, and Khubilai Khaan, are often misspelled in English sources. What steps can we take to address this issue? In your opinion, what key challenges in Mongol Studies should we prioritize to ensure a stronger presence in the international sphere?

JW. This is a challenging question for me personally. As a scholar, I tend to favor Mongolian spellings, but when writing for a wider audience, I recognize that many are accustomed to older spellings. An editor once told me that if I used the Mongolian spelling on the cover of my biography of Chinggis Khan, most readers would mistakenly think it was about a Chinese general. Therefore, I opted for the older spelling while explaining in the book that the Mongolian spelling and pronunciation differ. This is a compromise, but I hope that over time, foreign audiences will become more familiar with Mongolian spellings.

AJ. Could you share your writing process and the authors who inspire you?

JW. When writing about Mongolia, I seek inspiration and guidance from both ancient sources, such as The Secret History of the Mongols, and more modern works, like the poetry of D. Natsagdorj and the music of composers B. Sharav and D. Jantsannorov. These artists understand the Mongolian soul and character far better than I do, and they serve as my teachers and guides.

AJ. As a pioneer in your field, introducing new theories that shift global perspectives must test your resilience in getting published. What practical advice would you give to your younger self for overcoming challenges as a writer in international publications?

JW. I am completely confused by the modern publishing environment. My recent book on the Mongols and the sea was rejected by 17 American publishers, who claimed that my style was too old-fashioned or that I wasn’t connected to a modern audience that prefers more action than explanation. Fortunately, Bloomsbury in the UK took a chance on me and published the book. Now, we wait to see what happens.

My advice to young writers is to know your subject as thoroughly as possible. Writing should reflect knowledge rather than mere opinion. Many modern writers begin by publishing online, and I acknowledge that any fifteen-year-old in Mongolia likely knows more about this than I do.

AJ. In 2022, you received the supreme decoration of the Mongolian State, the Order of Chinggis Khaan. In your speech, you expressed that “This is the century when Mongolia can help the world move closer to the dream of Chinggis Khaan. Mongolia is the center of world history, the homeland of Chinggis Khaan, and you are the guardians of his memory and legacy.” Could you share your vision for the future and the direction in which you would like to see Mongolia grow as a country?

JW. Even before the time of Chinggis Khaan, the steppe nomads knew how to interact with people from every nation, culture, language, and religion. This unique trait persists today. Mongolians have always had the ability to absorb the best influences from other societies while maintaining their own distinct path in life. They incorporate ideas but do not imitate. No other country can serve as a role model for Mongolia, but in forging its own way forward, Mongolia can become a role model for many other nations.

As long as Mongolia looks to its past great leaders for inspiration, it can serve as a beacon to the world. Today, perhaps more than ever, the world seems lost and without a vision. Chinggis Khaan had a vision, and that vision can help guide both Mongolia and the world forward.

We are now in the ninth century of Chinggis Khaan’s Mongolia, and it has the potential to be its greatest era.

Mr. Weatherford, it is an honor to have this opportunity to interview you. Thank you very much.

Emperor of the Seas: Kublai Khan and the Making of China will be released in all major bookstores worldwide and translated into French, Russian, Spanish, Korean, Mongolian, and Chinese, with separate editions for Taiwan and a few other languages.

J. Ariunaa

Published in UB Post

October 14, 2024