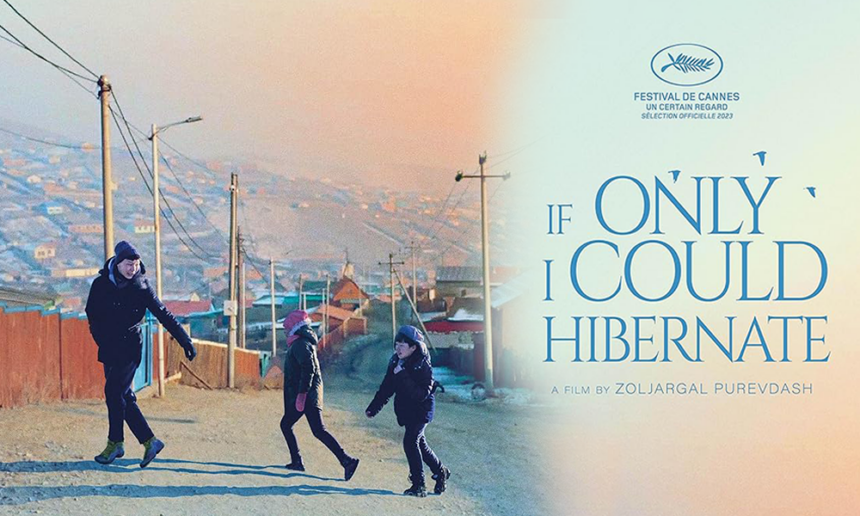

Zoljargal Purevdash’s feature film If Only I Could Hibernate is certainly a critique of the vast gap in economic inequality. The film captures the conditions of precarity of the ger district residents, and the menacing air pollution caused by a lack of infrastructure in the peripheries of the city. A long-standing thorn in the eyes of both the upwardly aspiring middle class and the oligarchic grandees who dwell in the luxury comforts of heated apartments there is a type of “no clue” disregard, as poignantly captured in the film, for the poverty-ridden fellow city dwellers who are sometimes reduced to burn whatever comes in handy. The director’s intention, as mentioned in one of the interviews given to one film review site, is however optimistic and sees education as a way out from the abject conditions that the wasted youth (and brains) are subjected to. Perhaps because of such an element of optimism, many of the review sites give parallel reference to the Hollywood-produced Good Will Hunting. The goal of the film in the words of the director is pragmatic as she mentions in one of her interviews that “education is also being able to calculate finances and measure one’s sexual education.”[1] One could aim for such development of the self if it is to maximize one’s potential in a system plagued by disciplinary rhetoric of neoliberal marketized personhood. However, I think the film achieves something beyond the author’s intention.

Theoretical physics is the subject that the film unconsciously extrapolates beyond the authorial intention and to understand how, I need to give social and cultural context in which this interest is pursued.

A few years ago, Mongolian news media sensationally informed the public how there is a lack of enrollment in the Department of Theoretical Physics at the National University of Mongolia, where the brightest used to be admitted. One of the faculty members lamented that he has now only one student enrolled in the physics program thus rendering this nomenclature of knowledge a near-extinct species. This, he informed on the media, is because the majority of the brightest choose to study business and law. Mongolia’s theoretical math and physics departments were created during the heyday of state socialism and were heavily influenced by the scientific developments in the Soviet Union. Hence the film offers a glimpse into I. I. Sokolov’s textbook on the methods of teaching theoretical physics.[2] Now to get to the point, the film achieves something beyond its intention by specifically dwelling on something as useless and rendered obsolete as theoretical physics in the competitive free market economy, a popular mantra which has come to dominate Mongolian imagination since the 90s. The competition that the film highlights throughout the film is not a competition for the extraction of profit but for the hopes and dreams of acquiring a scholarship into a prestigious school and maybe an opportunity to study abroad. Instrumentally this is as far as the development of the plot can suggest since we don’t really know what happens if Ölzij, the teenage protagonist goes as far as to be able to get admitted into leading universities in the West. Who knows what happens after his eventual PhD in theoretical physics, will he join the famous Fermilab and will he choose to live a comfortable academic life in Switzerland or America’s Midwest?

This dialogue-ridden plot development is, however, subverted by far more intelligent images which capture the boy’s potential disinterested interest in science. In a dialogic frame which depicts Ölzij’s physical exhaustion from illegal logging, a trade which he picks up to make ends meet due to the absence of his alcoholic and somewhat incompetent mother, he exchanges his gaze with Sokolov’s textbook. It is obvious that even when the harshest of the realities of social condition threatens to engulf the entirety of his subjecthood there remains something to resist it with. It is a desire that has not yet been consumed by a sense of survival and which has not yet been instrumentalized.

His desire remains pure, and which is acknowledged by his teacher, once a brilliant student himself who decided to exit academia to teach in a peripheral city school. Ölzij’s dreams and desires could have perished and perhaps assumed another wasted end as reminded by the presence of his pal who ended up giving up on his education by switching to a hustler lifestyle, or his mother who for unknown reasons chose not to pursue education. It is only through a glimmer of extraordinary solidarity shown by his elderly neighbours and the sheer determination of his physics teacher to help the boy that Ölzij can advance to the finals of the national physics competition. In the times when one’s blood affines such as his mother and his aunt’s activities cannot escape their social conditions such as blind superstition, or hopelessly aiming to sell one’s labour for a meager income which result in a terrible family alienation, we find solidarity in the most unexpected moments of kindness and human compassion. The film’s moral purpose unmistakably highlights this remarkable potential for human solidarity.

As a final remark, it will only do justice perhaps to invoke the haunted specter of Karl Marx. This is because Mongolia’s modern history of the development of scientific branches of knowledge were heavily influenced by the Leninist version of Marxism which sought to appropriate the greater achievements of human history whether arts or sciences for the human good, and not for profit. Also, the dreaded capitalist economy which Mongolia by chance managed to escape due to the “bypassing of capitalist stage of development” throughout the twentieth century has finally caught up with the country’s economic liberalization. Marx who worked in the conditions of abject poverty himself and who finished his manuscript on the relations between economic production and its effects on human social condition, remarks Terry Eagleton, was a great romantic who admired poetry and literature.[3] His critique of economistic thinking was founded on the belief that humans are essentially creative, aspiring, and curious beings but that potential cannot be fully realized when our imaginations are colonized by marketized thinking. Theoretical physicists are poets too. They doggedly pursue interest in science not because they dream of owning some sort of corporation but because many of them continue to do so because of the sheer delight of understanding the magical art of the universe which unfolds and expands in its myriad mysterious ways the frontiers of human imagination.

The film made Mongolia-wide opening yesterday.

[1] See the director’s interview on the Variety site. https://variety.com/2023/film/news/if-i-could-only-hibernate-cannes-mongolia-1235621331/

[2] Not to confuse with another brilliant Soviet physicist Arseny Sokolov who was responsible for the Sokolov-Ternov effect.

[3] In a world plagued by instrumental thinking be like the silkworm which produces silk not for the extraction of profit but for the sheer beauty of it. Link to the article: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v45/n13/terry-eagleton/be-like-the-silkworm

2024.01.13