Part 2 of 2

The 18th century Tibetan Buddhist Dagpu Luvsan Dambiijaltsan was the reincarnation of the Indian Prince Dharmanand. [3] Somewhere between 1735 and 1737, at the request of his students, Dagpu Luvsan Dambiijaltsan wrote down the dreams and visions he had since he was 11 years old. The book was titled, “The Tale of the Moon Cuckoo with a Blue Voice.” Its aim was to help readers understand the significance of compassion. About a century later, Noyon Khutagt Danzaravjaa wrote an opera based on this story in Mongolian. It is a legend about why the song of the cuckoo bird ushers in the beginning of spring.

The Legend

Once upon a time, there lived a noble king, Gularanz with his noble queen, Makhamadi. [2] They had a beautiful son named Nomuun Bayasgalan. The king’s adviser, Yamshi was jealous of the young prince. He set the prince up for a quarrel that chased away all his confidants. Then, Yamshi introduced his own son, Lagan, who became the Prince’s only trusted counsellor. Nomuun Bayasgalan was engaged to the lovely Sersenmaa, of whom Surasdini, her friend, was also jealous.

One day, Lagan convinced Prince Nomuun Bayasgalan to go into the deep forest and meditate with him. He dared the prince to switch bodies with another being. So, both transferred their souls into cuckoo birds and flew freely in the sky all day. But as the day was turning into night, the counsellor’s son suddenly abandoned the prince and flew back to the riverbed where their human bodies laid. Lagan quickly transported his soul into the prince’s body. Then, he threw his own into the river. When the lost prince finally found his way back to the right place, neither his friend nor the bodies were anywhere to be found.

The dazed prince flew back to his palace only to see that his body had indeed been stolen by Lagan. He tried in vain to speak to his parents, to anyone. People only heard a bird’s song. Lagan, posing as Nomuun Bayasgalan, declared to the king and the queen that his trusted friend had drowned in the forest river. Upon hearing the news of the death of their son, Yamshi jumped off a cliff, and Lagan’s mother hanged herself. But Lagan didn’t seem to be bothered. He continued posing as the prince, wreaking havoc on the king’s court. He rejected his lovely fiancée in favor of the terrible Surasdini. The uncharacteristic behavior of the prince pained his parents. The noble queen died soon thereafter. The king became disheartened. The kingdom went into an age of decline.

Sersenmaa had been noticing that ever since his return from the forest, her noble prince had become very cruel and intolerant. She tried to console the king and went in search for the real prince in the forest. After many days and months, she met a traveling monk, who had a cuckoo bird for a companion. The monk spoke of the sorrows of his feathered friend. The cuckoo bird was once a noble prince whose fate was stolen by a traitor, said the monk. So, he was helping the prince to pray for the wellbeing of all animals in hopes that someday his soul could return to his human form. Sersenmaa went back to the palace and consoled the king once more. The king implored the gods to transform him into a cuckoo bird so that the father could reunite with his son, but to no avail. Ever since then, the cuckoo bird sings prayers for a change in fate. That is why the cuckoo bird’s song has come to herald the beginning of spring.

The Opera

Noyon Khutagt Danzanravjaa’s “Life Story of the Moon Cuckoo” was staged from 1831 to the 1920’s throughout Mongolia and beyond with great success. When presented in its entirety, the opera lasted for a whole month. It consisted of nine acts. Its shorter version continued for 15 days. The audience would camp near the vicinities of the theater to watch the opera. This coincided with a joyous period of summer festivities. Every day, the show started in mid-morning and went on until lunch break, then finished sometime in the mid to late afternoon. In between breaks, there were dance and comedic performances, which the audience particularly relished. [4]

Danzanravjaa and his students would recruit the most talented singers and dancers amongst the general population. They would start rehearsals about half a year prior to the presentation. Women and monks were also allowed to participate in the performance. Danzanravjaa’s theater had a complex structure allowing assistants to create rain, winds, clouds, rivers, lights and the moon without the audience seeing them. The orchestra of musicians with traditional instruments played the sound effects and the music. The music and lyrics were composed by the playwright himself. There was even a special nook for the prompter to help actors who forgot their lines. The dressing rooms were hidden behind the stage. The actors wore bright makeup and extravagant costumes for a dramatic effect.

Danzanravjaa freely edited the original narrative, adding more color and contrast to the characters and their dialogue. Danzanravjaa scholar S. Khuvsgul counted that the opera had altogether at least 87 cast members. [1] Each role had many different bodies and costumes that represented its past, present, and future life. Every character was vital to the story that would not have been complete without it. The playwright created additional roles, including the role of the queen mother, Makhamadi. His female characters were complex. They had important passages to recite. It highlighted the agency and sensibility of women in the public eye.

The Message

Many scholars agree that Danzanravjaa’s version of the “Tale of the Moon Cuckoo with a Blue Voice” could be considered an independent work of art. His opera, in which nature and soul are considered as one, contained deeply philosophical and religious lessons from Buddhist teachings. It was also entertaining thanks to its comedic, romantic, and lyrical themes.

The opera treated at least three important concepts central to Buddhist philosophy. Firstly, it introduced the idea of oneness and the transcendence of the limits of life through meditation. Secondly, the opera depicted the manifestation of the laws of karma through the relationship of the prince and the counsellor’s son. In a way this seemed to justify the injustices endured by the main character. Finally, it is a tale about the significance of compassion and prayer for the alleviation of suffering for all sentient beings of nature.

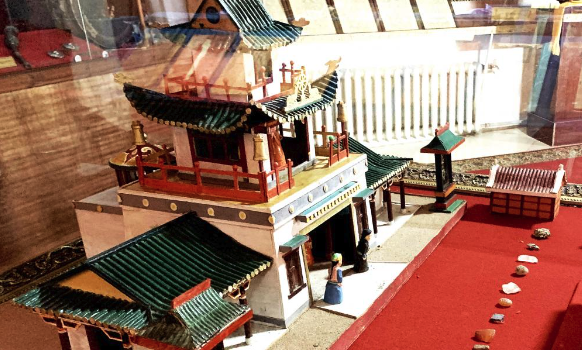

Today, Danzanravjaa’s museum in Sainshand, Dornogobi Aimag is home to the invaluable manuscripts, stage directions, the score with original musical notation, as well as costumes created by Danzanravjaa’s students. As historians and dramatists gain support and expertise in accurately studying this unique opera, they make crucial steps toward the revival of traditional Mongolian theater.

Let us hope that one day the restaging of Noyon Khutagt Danzanravjaa’s chef-d’œuvre will enrich the joyous period of summer festivities once again.

References:

[1] Khuvsgul, S. “Саран Хөхөөний Намтар Жүжгийн Дүрийн Тогтолцооны Онцлог.” In Tsedevdorj, G. Д. Равжаа Судлалын Тойм, Vol. 2. Ulaanbaatar: Bambie San, 2014. Pg. 154.

[2] Mend-Ooyo, G. Гэгээнтэн. Ulaanbaatar: Munkhiin Useg, 2012. Pg. 229.

[3] Muzrayeva, D. N. “Сравнительно-Сопоставительный Анализ Текста Биографий Дагпу Лобсан-Данби-Джалцана (XVIII B.) и Либретто Пьесы Д.Равджи “Жизнеописание Лунной Кукушки” (XIX B.)” In Tsedevdorj, G. Д. Равжаа Судлалын Тойм, Vol. 2. Ulaanbaatar: Bambie San, 2014. Pg. 216.

[4] Oyun, E. “Саран Хөхөөний Намтар Дуулах Тухайд.” In Tsedevdorj, G. Д. Равжаа Судлалын Тойм, Vol. 1. Ulaanbaatar: Bambie San, 2014. Pg. 82.

By Ariunaa Jargalsaikhan

Published in UB Post on January 20, 2021

Ulaanbaatar