Last week I traveled to Zavkhan aimag to climb Otgontenger, the highest peak in the Khangai Mountains, from its northwest side. The peak sits at an elevation of 4,031 meters above sea level, boasting snow caps to its south and a cliff to the north.

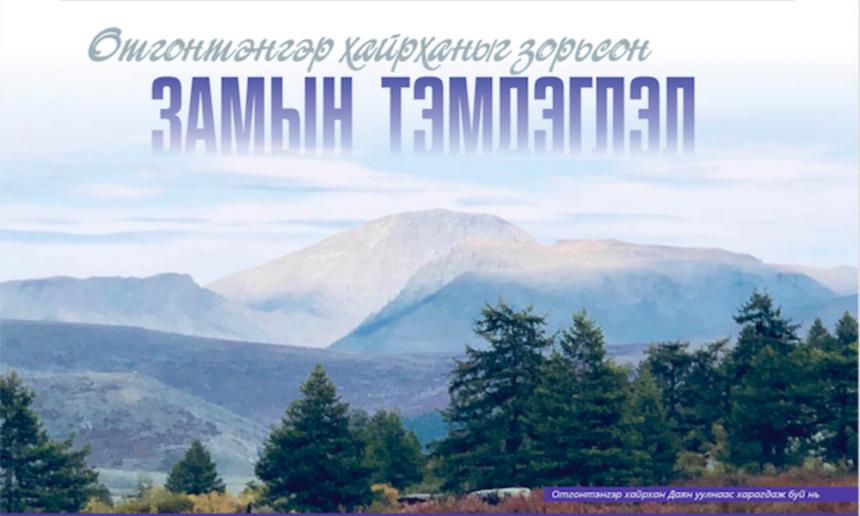

Following the state protection of nearly 1,000 square kilometers of land surrounding Otgontenger, people have not settled down or herded their livestock there. So the landscape looks beautiful and untouched. When we traveled 100 kilometers to the southeast of Uliastai and climbed Mount Dayan, we could not help feeling enthralled looking at a captivating view of Otgontenger in the distance under a clear blue sky.

Zavkhan aimag showcases beautiful nature with a perfect mix of Khangai and Govi, which is the reason why there are many tourists not only from abroad but also from other parts of Mongolia. The territorial area of Zavkhan is nearly the same as Austria’s – 82,500 square kilometers, and a total of 80,000 people live in the province. I wanted to share some thoughts and observations I reflected on while traveling on the road to Zavkhan.

Road at Zagastai mountain pass

A herder who is spending the summer nearby the lake of Terkhiin Tsagaan in Tariat soum of Arkhangai aimag said that he now believes roads actually bring development with them. He and his family have found good income this year as they have been catering for travelers from Ulaanbaatar. These travelers have come in great numbers this year, given that a newly paved road has been commissioned.

However, it is a different scene over in Uliastai, the center of Zavkhan province. People there have been waiting for the promised development for many years. The paved road from Ulaanbaatar runs nearly 1,000 kilometeres and has actually reached Tosontsengel soum of Zavkhan aimag. But the roadwork is still not finished, which forces travelers to drive on a bumpy dirt road for 30 kilometers. Then you suddenly get back on the paved road and drive on a smooth surface for 100 kilometers passing by Telmen soum. But then once again it is the end of the paved road when you get to Zagastai mountan pass.

It is approximately 67 kilometers from Zagastai to Uliastai, but it is such a challenging trip on the dirt road that tests skills and resilience of both drivers and the vehicles they are driving. The journey is full of steep and sudden turns and countless bumps of varying sizes and impacts. We drove for two hours in the night to finish the journey. Later we learned that many companies have been selected over the years to build a paved road here. When the government was replaced one time, the loan from the Development Bank was suspended and an expectation was created that the funding would come from the public budget. But it never did, and the roadwork was postponed for several years. It was only last month when a resolution was reached to get funding from a loan from China Eximbank, and the work would be completed by a Chinese company. But still, if the 2019 public budget allocates 2.5 billion MNT into this work, the road can be completed in 2020.

The people of Zavkhan are counting the days for the road to be completed in 2010 and for the development it is expected to bring. If the road had been built ten years ago as it was planned from the beginning, the overall labor productivity would have been reinvigorated and so would have been the business environment and tourism industry.

Zavkhan’s roads are a clear example of how the government has been cutting the budget for roads when they had to spend one fourth of budget revenue to make interest payments that came from the poorly estimated loans they raised.

Bogd River power station lighting Zavkhan

Zavkhan used to get their electricity from diesel generators for limited periods because there was no continuous supply of electic power. In 1994, Mongolian engineers built a hydroelectric power station at the bank of Bogd River, which has a fast flow. In 2005, the power station was upgraded with financial aid from Germany. Since then Uliastai has an uninterrupted supply of electricity in the summer and gets power from the Taishir power station in the winter.

The Bogd River power station is located 36 kilometers to the southeast of Uliastai and has a capacity of 2 megawatts. It draws the water from 2.5 kilometers in several channels and uses the natural flow to fill up a pool on a hill. Two big pipes are placed on the side of this hill and connect with a turbine that produces electric power. The water flowing from a height of 17 meters in the east of this hill has become a manmade waterfall that has its own beauty.

This is one of Mongolia’s 11 hydroelectric power stations that use the fast flow of water found naturally in rivers. It was evident that Zavkhan has a vast potential to develop electric power, manufacturing, and the tourism industry if they play their cards right.

Tsenkher’s hot spring and its unregulated camps

From Ulaanbaatar we drove 480 kilometers on dirt road and another 30 kilometers on dirt road to get to the famous Tsenkher’s hot spring. In terms of its temperature, Tsenkher’s hot spring is the second hottest in Mongolia, only behind Shargaljuut, and has a flow rate of 10 liters per second. The water from this hot spring contains elements of hydrogen, sulfate, and flint, which is said to have soothing powers that help the human body, health, stress, and diabetes.

Tsenkher’s hot spring has at least five recreational camps – Tsenkher jiguur, Shiveet mankhan, Duut resort, Khangai resort, and Altan nutag – sitting beside each other. They all have a channel from the source of hot spring and fill up their own small pools every morning and release the water every evening. You cannot find accommodation in these camps unless you make a reservation well ahead. In total, together they can accommodate nearly 500 people a night. However, it looks like they have not quite found an effective way of working together to improve the environment, roads, and public areas.

When you have 500 people spending the night and one hundred cars being parked in the premises, it means you are a settlement. We could see that nature and the environment there were deteriorating unless they do some proper planning and build paved roads, proper parking spaces, and resolve fresh water and sewage pipelines.

It is time to develop and implement legal regulations that require registration of countryside camps and resorts at aimag level, and to make sure that tax income stays with the local soum government so that they can spend the money on improving infrastructure.

‘Penguins’

We saw many different birds on our 1,000-kilometer journey from Ulaanbaatar to Uliastai. However, the biggest and most curious ones were the ‘penguins’ who sat along the road one after another.

People are forced to turn into ‘penguins’ because there are no public restroom facilities. We could have built dozens of pit stops that have restrooms and serve snacks and coffee, when the road was first built. A standard on how to build such facilities was even passed in 2005 under the name ‘Mandatory requirements for facilities to serve people on the road.’

Therefore, we need to start tendering out permits to build those service facilities along the road – perhaps one every 100 kilometers. This can be supported by local governments and encourage tourism.

Besides building infrastructure, every aimag needs to create its own unique brand. If all aimags develop their own tour programs that are based their own folklore, heritage, and culture, we have a great opportunity to develop tourism, which will in turn help local people and businesses economically. This could then eventually reverse the migration from the countryside to Ulaanbaatar.

Development follows roads. It is time to start planning wisely, encourage people’s involvement, and give the aimags economic freedom.

2018.08.29

UB-Uliastai-UB

Trans. by B.Amar