Dzud: Quiet Devastation of Livestock and Livelihoods

Chagnaadorj, a nomad whose family comes from a long ancestry of resilient Mongolian herders, is proud of his heritage. The now 50-year-old recalls his grandfather’s stories of living under the country’s extreme weather conditions. However, this year is different. Heavy snowfall, blizzards, and arctic-like temperatures make “dzud,” a harsh winter, one of the most severe recorded in modern history.

Nationwide temperatures have dropped to below -30°C and the highest levels of snowfall in 49 years. These conditions have impacted the livelihood of Chagnaadorj’s family but also highlighted the true spirit of these proud Mongolian herders.

“There might be something that our ancestors never saw coming, which could challenge us. We are powerless against nature’s force.” his voice trembled ever so slightly, not due to the challenge of the weather but how these extreme weather conditions might impact his children’s future.

Mongolia’s climate is changing. This is the harsh truth. Herders and nomadic farmers are all witnessing enhanced seasonality. That means the four seasons of every year display significant temperature fluctuations and minimal precipitation, which is terrible for livestock, and this industry already has harsh margins. A unique reflection of business mirrors its very environment.

In addition to more extreme seasonality, there are increasingly severe winters called “dzud,” a unique natural phenomenon in Mongolia where heavy snowfall and extreme cold follow the summer droughts. As a landlocked country with harsh continental climate conditions, Mongolia embodies Mongolian legends of the Steppe. However, the lush grasslands also make this country an excellent breeding ground for lamb.

The Eurasian continent, with its high elevation above sea level, encirclement by towering mountains, and a considerable distance from the sea, all set the foundation for great farming. Minerality in the soils, thousands of years of nomadic culture, and today’s social and political factors not only enable the perfect nomadic lifestyle but are also being threatened.

Herders like Chagnaadorj accept the dzud and worry about future conditions. However, they are also faced with the homegrown, domestic threat of readiness and vulnerability to adapt to climate (and other) change. Mongolia is considered vulnerable to climate change impacts, ranked 67th out of 181 countries in the 2020 ND-GAIN Index.

This index measures a country’s current vulnerability to climate disruptions and assesses a country’s readiness to leverage private and public sector investment for adaptive actions. This translates to a need for action from businesses and governments when it comes to helping the nation prepare itself for climate change, which will significantly impact Chagnaadorj and many other nomadic communities across Mongolia.

In perspective, in March 2024, livestock losses nationwide were reported to be nearly 2.9 million from the previous winter. This is huge and would have impacted the livelihoods of thousands, not only the nomadic herders but also the butchers and individuals working in the supporting or periphery industries. It had gone down to the worst situation since the winter of 2009 when herder households from 20 of the 21 Mongolian provinces faced huge losses.

It is not all doom and gloom, as the Mongolian herder and farmer community are a unique breed. They have survived thousands of years and have the additional technology assets today. However, this does not overshadow that in the past 30 years, Mongolia has lost 21.1 million head of livestock, amounting to 860 billion MNT.

The very future of Mongolia, or at least its spiritual profession of nomadic farming, is in danger through negligence and mother nature. Thirty percent of Mongolia’s total population of 3.5 million derived their livelihoods from livestock herding, and if this were to be further disrupted, the whole nation’s economy would face the impact.

There is also a man named Shinebayar alongside the likes of Chagnaadorj. As one would expect from a Mongolian herder, he is hardened and seasoned. Physically impressive, with rugged skin and a strong, upright posture, it becomes evident that he has dedicated most of his life to working in some of the harshest conditions on the planet.

Despite his physicality and near spiritual proximity to his craft, the 42-year-old herder from Arkhangai province in central Mongolia watched helplessly as his livestock dwindled from 300 to 30 – in just a few days. He, too, was not saddened by the impact on his pocket (profit) but by the impact that losing such numbers would have on his family of three children and wife.

These men do not go into the profession of herding for the money, but now he admits, “We are left with no option but to relocate to the city. We are at a loss for what to do next. Our lives have been devastated in just one winter.”

Chagnaadorj and Shinebayar spend every day outdoors, exposed to all seasons, including nighttime. In his 20 years of herding livestock, he has noticed a significant problem – the weather is changing faster because of climate change. Shinebayar says, “Forecasting seasonal changes is getting extremely hard.”

“In addition, we are worried about repaying our herder loans.”

Moreover, this is where the story begins: if each herder is taking loans, and for decades, these have been repaid and sustained with sustainable weather and herding, the current and recent loans will cause economic havoc.

Chagnaadorj and Shinebayar are just two examples of many herders who have been faced with relocation to the cities. Herders have no assets other than their livestock, unlike other farmers in other nations, which many balance income and debt leveraging with land or property.

Given that this is the first instance where climate has led to such a significant issue, it prompts questioning and possibly forecasting the salaries and duration of work for herders relocating to guild districts—and whether it will ever suffice to cover the debt for a herd of sheep.

This has created a knock-on effect on several other industries in Mongolia, including the creation of this expanding debt bubble. These are all questions both banks and the Government will have to ask, even as they defer payments and reduce amounts, but it shows that change comes from the pocket and not through the morality of doing it for the right thing.

As we see, the age and assets of the farmers are also worth considering. Their unique skills and character may need to be revised to reintroduce them to urban or office settings. Chagnaadorj, the 50-year-old herder from Zavkhan province, recounted the struggles faced by his family of six.

He married in 2003, and since then, his family tended to a flourishing herd of 1300 livestock. However, this winter obliterated both his herd and his family’s lifestyle. The relentless snowstorms imprisoned them in the family ger, a round nomadic tent covered with layers of felt.

At the same time, those causing the climate change or in positions to help mitigate it enjoyed the relative luxury of Ulaanbataar’s developed infrastructure and luxury districts. These policymakers, lobbyists of the mining companies, and financiers were probably oblivious to the hardship faced by the herders out in the wilderness.

This last winter did not arrive quietly. It stormed across the Mongolian steppe, much like the Mongol hordes of ancient times. The grasslands turned to fields of fallen sheep, murdered by freezing temperatures, and in many cases, the herders alongside them. Somehow, Chagnaadorj and his family made it.

After the harshest night in many months, he surveyed his herd and counted his losses. “We are lucky enough to be losing only up to 50 livestock this winter,” he remarked to his wife, Bolor. The pair remained spirited despite knowing they were facing a losing battle.

Every year was getting worse, and as they went about their activities, he mentioned, “But there is no guarantee that we may not lose more and more in the upcoming years.” This showed a sense of acceptance of how nature, forced by humankind’s activities, was becoming increasingly harsh. As the refusal persisted, the winters grew colder, and the summers grew hotter. The previously abundant grasslands turned dry and brittle.

“Our livestock is all we have,” Chagnaadorj sighed.

Later that year, Chagnaadori considered the Government’s pledge to relocate and accept the offer of reduced interest and repayment, sell what was left of his flock, and requalify for a trade in the city.

***

The herder’s final migration?

Ulaanbaatar, founded in 1639 as a nomadic Buddhist monastic center, now a city on the brink of extremes, is a place of enormous contrasts. 841,000 live in apartments, and 797,000 live in the ger district. Most individuals living in ger districts are local migrants and herders seeking refuge, employment, and a new life.

However, they still cannot escape the impact of climate change. They have constructed their nomadic tents, but they need to be more suitable for modern city living. Pollution, urban planning, and policy have once again let the herders, who were once the lifeblood of Mongolia, down.

Ger districts need infrastructure improvement, with many needing access to clean water, sanitation facilities, centralized heating systems, and restrictions on what they can do. In short, they have swapped their freedom for a harsher life than those facing dzuds and unpredictable seasonality.

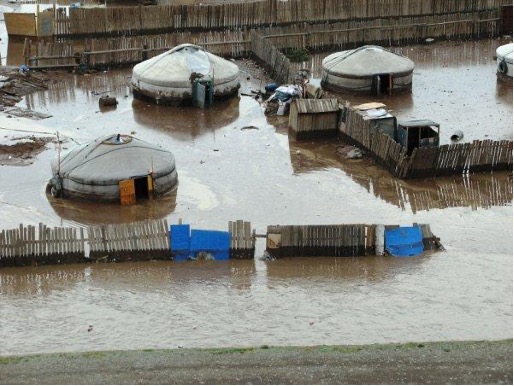

A citizen of Songinokhairhan district, Adya, moved to Ulaanbaatar city from Arkhangai province, located in the country’s central region, renowned for its beautiful landscapes. He was sold on the promise of opportunity but had yet to learn what awaited him in 2023. It was in mid-July of last year, as he sat at home, that he made the decision.

“I thought it was just rain,” he muttered, staring at what remained of his life. “I never imagined it could be this destructive. Twenty minutes, and it has all gone. Life can vanish in the blink of an eye.”

“It is a reminder that the threat of climate change is not knocking at our doors, but it is already in our homes, moving our homes and disrupting our lives,” he said. The houses he comes from are depicted below, but it only further shows the drama that tic change is needed, and this is an issue that both Chagnaadorj and Shinebayar face.

***

Key Takeaways

2023 was the warmest year since global records began in 1850.

During winter, households in the ger area burn substantial amounts of coal, contributing to 60 percent of the city’s air pollution, making it one of the most polluted cities in the world.

By 2050, it is estimated that livestock losses may increase by 50 percent, according to the Mongolian Environmental Transition (MET) report of 2018.

“Dzuds” are significantly affecting the economy, with Mongolia’s GDP decreasing by up to 0.9 percent or 846 billion MNT annually compared to a scenario without it. Moreover, 35 percent of the nation’s workforce is engaged in agriculture, and 7.0 percent of the country’s exports are derived from this sector.

Rapid urbanization has occurred in recent years, with 68.5 percent (2019) of the country’s population living in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar.

***

Tragically, herders are thrust into a cycle of vulnerability as herders move to the city, only to encounter another climate hardship. Winter robs them of their livelihoods, driving them into urban areas for safety. However, when warmer months come, floods sweep their fragile homes away, leaving them in dire straits again.

Mongolia is one of the world’s last surviving nomadic countries, and these stories underscore the harsh reality of rural-to-urban migration amidst the challenges of climate change in Mongolia. The increasing challenges confronting herders and their families have led to a significant migration to the cities.

Mongolia faces a rate of warming three times faster than the global average, with an increase of 2.25 degrees in the last 80 years, and it has been identified as one of the country’s most rapidly affected by climate change.

The acceleration of global warming, primarily driven by human actions through emissions of greenhouse gases, is causing irreversible harm to the environment and society.

Recent assessments have revealed that the global economic impact of natural disasters has exceeded the 30-year average, surpassing safety thresholds. “These are pledged for herder’s loan as an asset. Before losing it all, I am planning to sell and move to the city.”, shared Chagnaadorj.

Contemplating the future amidst such adversity, Chagnaadorj expressed uncertainty. He pondered the possibility of selling their livestock and resettling in the city if such conditions persist.

His decision to sell his livestock and relocate brings him uneasiness, having to leave behind decades of hard work for an uncertain future in the capital.

While the possibility of selling livestock brings the couple hope to secure their children’s education, uncertainty looms regarding how long their resources will last and whether they can continue to provide a promising future for their family.

“Through generations, Mongolian nomads have weathered the harshest of winters, fiercest droughts, and most devastating floods, demonstrating an unparalleled resilience,” Chagnaadorj remarked, his voice tinged with admiration for his heritage. However, his eyes reflect pride, worry, and determination as he worries about the adverse effects of environmental conditions.

It is projected that these severe winter weather events will occur every five years, twice as often as in the past. By 2050, it is estimated that livestock losses may increase by 50 percent, according to the Mongolian Environmental Transition (MET) report of 2018.

“Dzuds” are significantly affecting the economy, with Mongolia’s GDP decreasing by up to 0.9 percent or 846 billion MNT annually compared to a scenario without it. Additionally, 35 percent of the nation’s workforce is engaged in agriculture, and 7.0 percent of the country’s exports are derived from this sector.

Dzud has led to the heartbreaking reality of hundreds of thousands of herders abandoning their traditional lifestyles and migrating to urban centers. Rapid urbanization has occurred in recent years, with 68.5 percent (2019) of the country’s population living in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar, of the 1.7 million citizens living in ger districts.

It is projected that these severe winter weather events will occur every five years, twice as often as in the past. By 2050, it is estimated that livestock losses may increase by 50 percent, according to the Mongolian Environmental Transition (MET) report of 2018.

“Dzuds” are significantly affecting the economy, with Mongolia’s GDP decreasing by up to 0.9 percent or 846 billion MNT annually compared to a scenario without it. Additionally, 35 percent of the nation’s workforce is engaged in agriculture, and 7.0 percent of the country’s exports are derived from this sector.

It has led to the heartbreaking reality of hundreds of thousands of herders abandoning their traditional lifestyles and migrating to urban centers. Rapid urbanization has occurred in recent years, with 68.5 percent (2019) of the country’s population living in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar.

Land Degradation: A Threat to Livelihoods Yet Integral to Human Activities

Mongolia’s grasslands are under threat due to climate change and mismanagement.

Despite being disproportionately affected by climate change, herders must also take responsibility for their role in soil degradation through unsustainable husbandry practices.

Mongolia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism indicates that desertification and land degradation have impacted approximately 77 percent of the country’s land. Moreover, 362 rivers, streams, lakes, reservoirs, and springs have dried up as of 2022.

“In recent years our herders lack essential knowledge and experience in pasture management practices, unaware of their negative impact on soil degradation and overall climate.”, said Baasansuren, a representative of the National Emergency Management Agency of Mongolia.

With the collapse of the socialist system and the dissolution of state-owned cooperatives during the 1990s, livestock underwent privatization, while the land remained under state ownership.

In contrast to its human population, Mongolia is home to over 70 million livestock, including 32.3 million sheep, 29.3 million goats, 4.7 million cattle, 4.2 million horses, and 0.5 million camels.

Notwithstanding a steady rise in livestock numbers, the tradition of collaborative herding was abandoned. Consequently, the overgrazing of pastureland, fueled by an excessive livestock population, has led to significant degradation over the past two decades.

“Mongolian herders have been focusing more on increasing the quantity of their livestock rather than enhancing their quality”, Baasansuren noted. “So, they suffer greater livestock losses during “dzud.” By prioritizing improvements in quality and pasture management, they could potentially mitigate the risk to a certain point.”

“Livestock husbandry is a significant factor causing soil degradation. About 70 percent of the total area of our country is covered by pastures, and the plants in the pastures are also responsible for absorbing carbon dioxide”, continued Baasansuren.

In case the vegetation is degraded and dried up, and further desertification occurs, heat will be generated on the soil. So, for a country like Mongolia, it is necessary to scientifically approach the issue of livestock population, implement proper pasture management, and pay attention to the herd structure.

As climate change and human activities are cited as Mongolia’s primary causes of desertification, the Mongolian government attempted to address land degradation through the National Livestock Program, which includes official livestock targets. Based on the grasslands’ carrying capacity, these targets have been largely ignored, resulting in actual livestock numbers doubling the required levels.

Mongolia’s weather monitoring agency reports that strong winds and dust storms affect most parts of the country almost daily. The environment ministry attributes the rising frequency of yellow dust storms to desertification caused by climate change. This trend indicates a significant deterioration in the country.

Lastly, Baasansuren stressed that improved land management and husbandry alone will not have a vital impact on restoring the grasslands; only large-scale and complex initiatives can make a difference.

Ambitious Campaign to Combat Climate Change in Mongolia

3.4 Photo source: Mongolian Mining Journal

President of Mongolia, Khurelsukh Ukhnaa, initiated a nationwide movement to plant 1 billion trees by 2030. This initiative aims to combat climate change, Desertification, and deforestation while aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

In a bold stride towards environmental sustainability, the Mongolian Billion Tree Fund was established through collaboration between the Mongolian Bankers Association, Mongolian commercial banks, and the Bank of Mongolia to finance 34 projects with a budget of MNT 1.3 billion in 2023.

“This fund aims to finance exemplary green projects and foster collaboration with commercial banks to increase green financing and attract both domestic and foreign investment in the forestry sector,” stated Adiyasuren, a foreign relations and cooperation manager of the Billion Tree Fund.

The Mongolian Bankers Association (MBA) has pledged an annual donation of at least MNT 2 billion to the Fund. Additionally, plans are underway to plant 88 million trees and provide a loan of MNT 5.2 trillion, aiming to increase the green loan portfolio to ten percent within the banking sector by 2030.

Since November 2021, this initiative has already witnessed the planting of over 40 million trees across the country by October 2023.

“Our country’s commercial banks bring years of experience in project feasibility studies, making them key players in expanding this initiative and connecting with borrowers to promote carbon absorption, improve water resources, and drive climate-friendly business growth through soft loans,” she continued.

However, Adiyasuren emphasizes the importance of supporting businesses in achieving long-term environmental goals. Providing financing, skills training, and technology transfer are crucial steps toward enabling these businesses to play an influential role in environmental conservation initiatives.

Following a rigorous selection process involving professionals from 24 diverse fields, including Forest Protection and Education, 34 projects were chosen from over 200 submissions.

“One of our primary focuses is to educate as many people as possible about climate change, given the scarcity of experts in environmental fields. We have recently established a dedicated scholarship fund for students, which is currently in the approval process,” Adiyasuren noted, emphasizing the importance of investing in the next generation’s understanding and action on environmental issues.

Shortly, the initiatives are expected to generate 70 types of green jobs, introduce three new technologies, and educate more than 800 citizens on tree care practices. More than 7,000 forestry professionals need to be trained in a short period to plant a billion trees.

Moreover, it will concentrate on areas such as Green Spaces in Public Schools and Kindergartens, Community-based Afforestation, and Public Education on Ecology.

Planting a tree is simple, but nurturing its growth requires dedication and care.

When the campaign was launched, public perception was divided. Some doubted its feasibility, considering the monumental task of planting one billion trees quickly, especially in the face of harsh climate conditions like Mongolia.

Skeptics argued that such an endeavor seemed impossible, citing concerns about the available workforce and resources. However, doubts began to fade as the initiative gained momentum and communities rallied together.

Furthermore, an experiment utilizing drones with machine learning to facilitate tree planting is underway, signaling a technological leap in environmental conservation efforts.

The Mongolian government has devised a three-stage plan for the campaign, comprising a preparatory phase from 2021 to 2024, an intensification phase slated for 2024 to 2026, and a sustainable implementation phase scheduled for 2027 to 2030.

“Before this ambitious plan, our country’s environmental sector, particularly forestry, lagged. Now, public awareness has surged, and it has also become a catalyst for attracting foreign investment.”, Adiyasuren noted.

“There is still a long road ahead, but even if we do not meet the target, this initiative will remind people to care for nature. Mongolians are confronting the challenges of climate change, recognizing our nation as one of the most vulnerable in recent years.”, she added.

In 2022, Mongolia signed a memorandum of understanding with the European Union (EU), marking the country as the first in Asia to join the EU’s Forest Partnerships, aiming to enhance the sustainable management of Mongolia’s forestry sector.

Mongolia plans to host the 17th Conference of the Parties (COP17) of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in 2026.

by Erdenenyam.P